A Brief and Incomplete History of Secession in the United States

The idea of a part of a State breaking off from another part of a State is not unique. Vermont was formed from counties which seceded from New York in 1777. Until then it was just another part of New York. Maine seceded from Massachusetts in 1819. Until then it was just a part of Massachusetts even though there was no contiguous land connection, New Hampshire being situated between them. Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a State in 1820. This is partly why there are only thirteen original colonies, but they ultimately made sixteen of our current States.

The idea of a part of a State breaking off from another part of a State is not unique. Vermont was formed from counties which seceded from New York in 1777. Until then it was just another part of New York. Maine seceded from Massachusetts in 1819. Until then it was just a part of Massachusetts even though there was no contiguous land connection, New Hampshire being situated between them. Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a State in 1820. This is partly why there are only thirteen original colonies, but they ultimately made sixteen of our current States.

When the Constitution was written, Article 4 section 3 states that “New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” This language does not explicitly preclude the possibility of forming a new State from part of a single State, so Maine and West Virginia were both broken off from their original States after the Constitution was ratified. The division of Maine did have the ultimate but reluctant approval of the Massachusetts legislature. But the division of West Virginia was treasonous act and part of the act of aggression of the Union against the State of Virginia. In 1863 local Wheeling, Virginia politicians had colluded with the government of the North to stage a vote and break the western counties of Virginia into a new State. Many people whose sympathies were with the cause of the Confederacy would not vote because they did not recognize the United States government, while Federal troops had also driven many pro-Confederates out of their homes before the election, so the validity of the election is highly questionable.

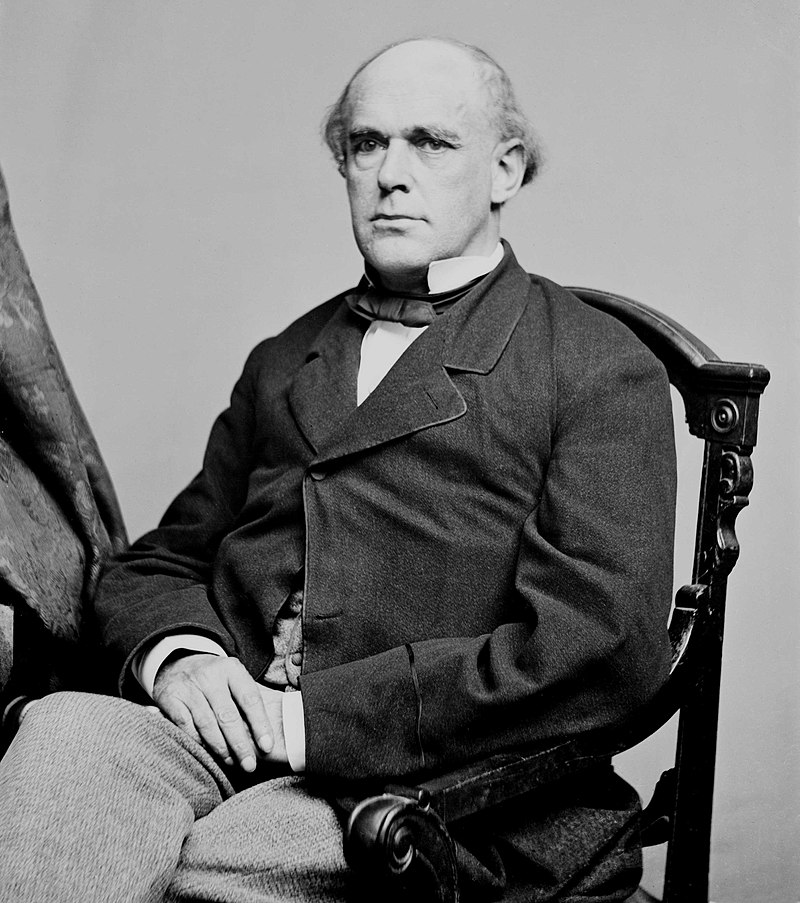

After Abraham Lincoln secured the Republican nomination for a second term in 1864, he accepted the resignation of Salmon Chase, his Treasury Secretary, who actually tried to resign several times earlier. Chase belonged to a radical wing of the Republican Party and he had been a challenger for the nomination in 1860. But while Lincoln did not want opposition in 1864, he nevertheless had to appease Chase’s constituency. So Lincoln then nominated Chase as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and he took office the same month, in December of 1864.

After Abraham Lincoln secured the Republican nomination for a second term in 1864, he accepted the resignation of Salmon Chase, his Treasury Secretary, who actually tried to resign several times earlier. Chase belonged to a radical wing of the Republican Party and he had been a challenger for the nomination in 1860. But while Lincoln did not want opposition in 1864, he nevertheless had to appease Chase’s constituency. So Lincoln then nominated Chase as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and he took office the same month, in December of 1864.

Salmon Chase may have done more damage to our cause as Chief Justice than he ever could have as President. In 1869 Chase presented a ruling in a case known as Texas vs. White in which he employed the “perpetual union” clause in the Articles of Confederation in order to declare the secession of any State to be illegal, or unlawful under the Constitution.

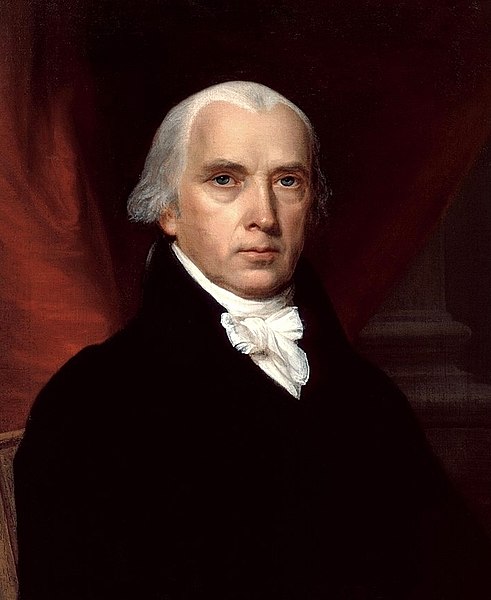

Where the U. S. Constitution had declared the will “to form a more perfect Union”, in the Constitution that union was not deemed perpetual. But in a twist of words Chase insisted that the phrase “more perfect union” meant to convey what had been expressed only in the Articles of Confederation. They certainly do not represent that idea, as James Madison’s words prove, and Madison having been credited with writing at least much of the Constitution certainly understood his own intentions and those of the other founders. But the decision presented by Chase had a 5-to-3 majority, and I don’t think the subject was ever revisited by the Supreme Court although it is clearly flawed.

In Federalist Paper Number 40, written in January of 1788, James Madison, the so-called “Father of the Constitution”, wrote of the Articles of Confederation and the “perpetual union” that they formed, and then in relation to what he called the “fundamental principles of the Confederation” he asked the question “What are these principles? Do they require that, in the establishment of the Constitution, the States should be regarded as distinct and independent sovereigns?” To that Madison supplied his own answer: “They are so regarded by the Constitution proposed.” This was six months before the new Constitution was ratified, and Madison was certainly not ignorant of the fact that the Constitution did not include the phrase “perpetual union”. That is precisely why Madison was writing that Federalist paper, because he was in support of the independence and sovereignty of the States against the “perpetual union” of the Articles of Confederation.

But there is a long-running argument in early political literature over which came first, the Union or the States, and it is reflected in John Quincy Adams’ famous speech on The Jubilee of the Constitution in 1839. [I erred on the date in the podcast.] Although Adams – who was also a President – was a Federalist, he acknowledged the sovereignty of the States but considered it a curse while he considered the Constitution a blessing. However Adams’ did concede that the “perpetual union” under the Articles of Confederation was “spontaneous, unstipulated, unpremeditated”, and he wrote that as a result the States had “relaxed their union into a league of friendship between sovereign and independent states.”

While I have certainly not read all the literature of the period, it seems that as they embarked on their campaign of aggression against the South, elements within the Yankee government never considered the possibility – or they purposely ignored the fact – that “perpetual” was purposely left out of a document which was created to replace, and not to augment, the Articles of Confederation. So in 1869 Salmon Chase was absolutely dishonest to cite the Articles of Confederation as if they actually had any effect or force in the law. They certainly did not, as they were replaced by the Constitution.

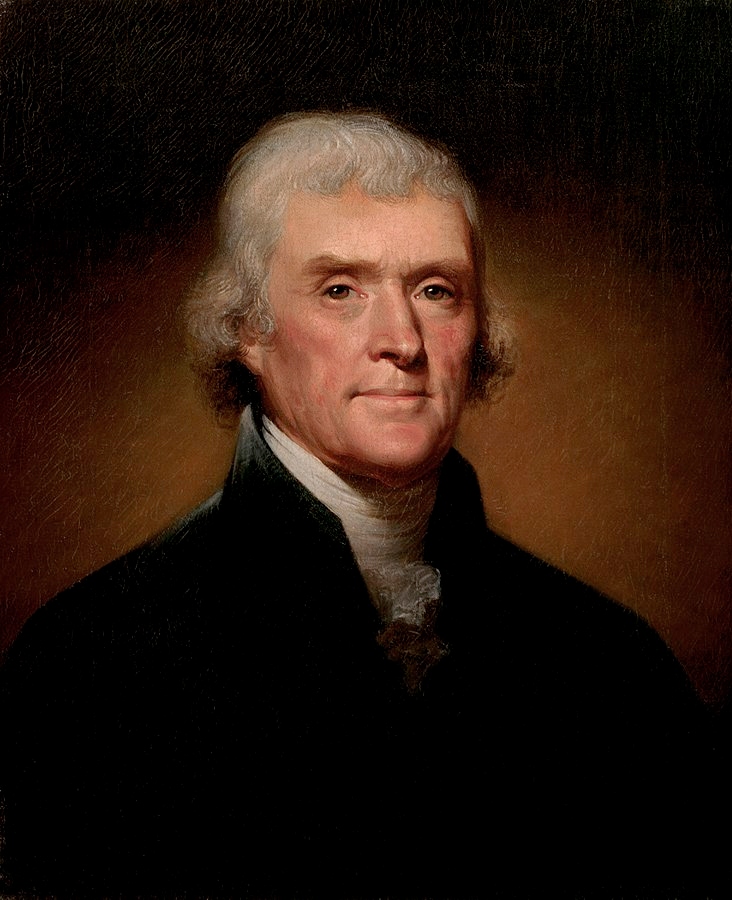

Like Madison, neither did Thomas Jefferson imagine that the Constitution created a perpetual union. Madison became president of the Union which he himself helped to create in 1809. In 1816, near the end of Madison’s second term, Jefferson wrote a letter to William Crawford, who was the Secretary of War, and he said: “In your letter to Fisk, you have fairly stated the alternatives between which we are to choose: 1, licentious commerce and gambling speculations for a few, with eternal war for the many; or, 2, restricted commerce, peace, and steady occupations for all. If any State in the Union will declare that it prefers separation with the first alternative, to a continuance in union without it, I have no hesitation in saying, ‘let us separate’. I would rather the States should withdraw, which are for unlimited commerce and war, and confederate with those alone which are for peace and agriculture.”

Like Madison, neither did Thomas Jefferson imagine that the Constitution created a perpetual union. Madison became president of the Union which he himself helped to create in 1809. In 1816, near the end of Madison’s second term, Jefferson wrote a letter to William Crawford, who was the Secretary of War, and he said: “In your letter to Fisk, you have fairly stated the alternatives between which we are to choose: 1, licentious commerce and gambling speculations for a few, with eternal war for the many; or, 2, restricted commerce, peace, and steady occupations for all. If any State in the Union will declare that it prefers separation with the first alternative, to a continuance in union without it, I have no hesitation in saying, ‘let us separate’. I would rather the States should withdraw, which are for unlimited commerce and war, and confederate with those alone which are for peace and agriculture.”

Thomas Jefferson correctly perceived the artificial corporations and engagement in the trade of corporate stock for ventures in commerce as ‘licentious commerce and gambling speculation’. That is what it is, when one buys a share of stock it is a gamble that a corporation will be profitable in the future. Jefferson also correctly understood that perpetual war in the name of corporate profitability was the only alternative to “restricted commerce, peace, and steady occupations for all”, and that was the choice which was set before the young country, just after the War of 1812. From the text of Jefferson’s letter it is also evident that Madison’s Secretary of War, William Harris Crawford, also knew these things. Crawford, a resident of Georgia who was born in Virginia, was a candidate for President in 1824 but finished third behind John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson.

Here in his letter, Thomas Jefferson also expressed the desire to see States such as Massachusetts and New York secede and go their own way rather than interfere with the “peace and agriculture” of the others, with whom he preferred to confederate. Evidently, Jefferson also must have thought that the Constitution should protect those States which only desired peace and agriculture.

But Jefferson’s words are profound, because ever since the Southern states seceded from the Union so that they could be left at peace with their agriculture, we have suffered under the first condition which he named, which is “licentious commerce and gambling speculations for a few, with eternal war for the many”. The devices of dishonest men like Salmon Chase have caused us all to become subject to the tyranny of the American empire initiated by Abraham Lincoln.